After reading David Örbring’s post (or in Swedish here) about knowledge in the Swedish curriculum, I thought back to my own experiences dealing with knowledge as part of curriculum design.

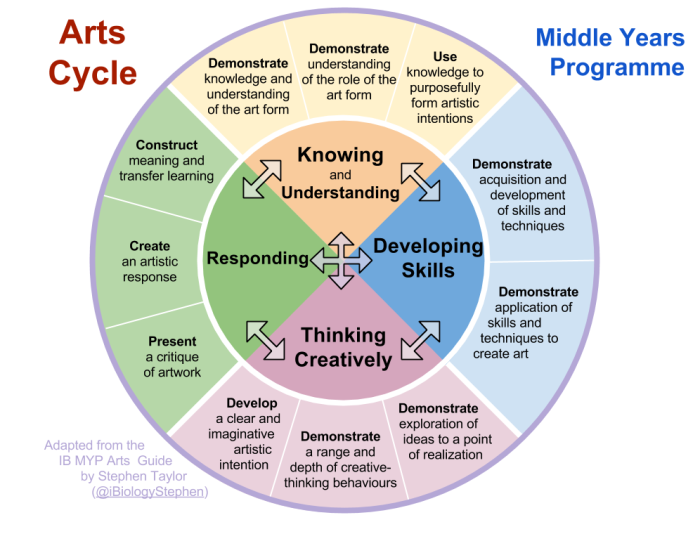

In my time as a music teacher, the most formative of all my experiences with “knowledge” was when I was a moderator for the International Baccalaureate Organization’s Middle Years Programme (MYP). In that role, music teachers from around the world sent me their lesson plans and students’ work so I could examine how well the teachers’ materials fit the MYP expectations and how well the teachers used the assessment criteria. The four criteria and their “strands” are shown in the image below. MYP is for students aged 11-16 (approximately, grades 6-10 or years 7-11).

This image is from a lovely blog by Stephen Taylor. He has published his own adaptations of the MYP curriculum with interesting connections between them here.

In the MYP Arts courses, “knowledge and understanding” is put on equal footing with “developing skills” similar to David’s description of curriculum goals in Sweden. But there are two further parts to this circle: “responding” and “thinking creatively”. Despite the intentional focus on creativity, when teachers sent me their plans and students’ work, this tended to include mostly written worksheets, journals, compositions, essays and recordings. Consequently, my most frequent recommendations were to improve the integration of the four criteria and not focus too much on parts that were easy to demonstrate in paperwork.

Perhaps because of the nature of the moderation process – usually frequent in the first few years of a school offering the MYP, where teachers with little teaching/planning experience focused on assessment and what could be sent through the mail – the samples were heavy on visible knowledge and skills. But this discounted the ways that knowledge is connected to responding and thinking creatively.

My response was to encourage teachers to reduce the amount of paperwork and to have their students think about how much knowledge they needed when they were creating or responding to music. It is difficult to respond to music with words if you don’t know any terminology. It is impossible to respond to music with your own creations without an understanding of the inner workings of music theory. Often the students knew more than what could be put on paper and their knowledge was intimately related to their skills, responses, and creativity.

The OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) is often criticized for its focus on what is easily testable (the criticisms are nicely summarized in this open letter to the OECD’s director of PISA published in the Guardian in 2014). PISA is criticized for being completely oriented toward the “know-what” rather than the “know-how”. Music does not make it into this test. But neither do the ways that knowledge is integral to more creative parts of education. So, unfortunately, the knowledge discussion becomes reductive, as if knowledge should be considered completely separate from creativity, or as if learning knowledge stops students from developing creativity.

In a recent study published by the Pew Research Center, they compared people’s perceptions in that country on whether it was more important to teach students “basic academic skills” or “to be creative”. A graph from their study can be seen below:

Image from the full article here

Somehow, this doesn’t tell the whole story. Looking at the Sweden split of 42% for basic academic skills and 54% for being creative (4% then said “both” or “neither”), it would be easy to assume that the Swedes are divided in their beliefs about what is important. But, from reading David’s post, it seems more likely that Swedes think that the two are completely intertwined and cannot be separated. When we look at the MYP graphic, the four areas all require knowledge and skills even though it is split into four areas.

Overall, there are no easy answers — but ‘what is knowledge?’ must always be part of the conversation between teachers, parents, students and anyone interested in education.